Static Linking and Dynamic Linking

Static Linking and Dynamic Linking

Top-Down Thinking Logic

The article "ELF File Format Analysis" provides some basics about executable and linking format (ELF) target files. Here comes a question: How do we link multiple compiled target files into an executable file?

Because each instruction in an executable file requires a clear address, the objective of linking is to determine these addresses for executable files. From this point of view, it is clear that the main tasks of the linker are:

- Allocating addresses and space to multiple target files

- Understanding the definition and reference of each symbol

- Modifying instructions whose addresses need to be updated

The three tasks actually correspond to address and spatial allocation, symbol resolution, and symbol relocation in a linking process. Symbol resolution and relocation are usually completed together. Therefore, this set of processing logic is also called two-pass linking.

According to the mode of allocating addresses and space to the target file, the linking mode can be classified into static linking and dynamic linking. The following discusses the details of the two modes.

Static Linking

Static linking means that before a program runs, the linker completes all relocation operations based on the relocation table in the object file and forms a program that does not need to load and relocate dependencies during program running in that all dependencies are linked to the program before running.

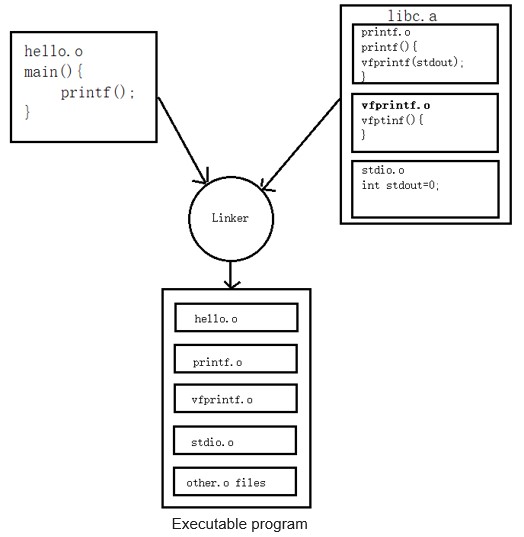

The following figure shows the process of obtaining an executable file through static linking. Find the target file printf.o in libc.a based on the header files included by the source file and the library functions used in the program, for example, the printf() function defined in stdio.h. (The dependency of the printf() function is not considered here.) Then statically link the target file to the hello.o file to obtain the executable file.

Static linking enables developers and teams to develop and test their own program modules independently, which greatly improves the program development efficiency. In addition, because static linking allows the executable file to have all conditions for program running, the program runs quickly during execution.

However, static linking wastes memory and drive space of a computer. For a multi-process operating system, each process uses many functions in public static libraries, such as the printf() and scanf() functions. As a result, duplicate public library function target files exist in the system memory and drive space.

Another problem lies in the difficulty of updating and upgrading programs. After a target file required by an executable file is updated, the entire executable file needs to be relinked, which is inconvenient.

To solve the preceding two problems, the easiest way is to separate modules required by a program and link the modules when the program is running, which is the basic idea of dynamic linking.

Dynamic Linking

Dynamic linking refers to the reference of the main program to symbols in dynamic shared libraries or objects, which are loaded and relocated when the program runs. The main program still uses static links. These links do not link the dependent dynamic shared libraries or objects to the main program.

Dynamic linking involves runtime linking and loading of multiple files. These operations must be supported by the operating system. Currently, mainstream operating systems support dynamic linking. In Linux, ELF dynamic link files are called dynamic shared objects (DSOs), and the file name extension is .so. In Windows, dynamic link files are called dynamic linking libraries (DLLs), and the file name extension is .dll.

The following illustrates the general process of dynamic linking in Linux. Three source files are required: hello.c, lib.c, and lib.h.

/* hello.c file */

#include "lib.h"

int main(){

printInLib(1);

return 0;

}/* lib.c file */

#include <stdio.h>

void printInLib(int i){

printf("Hello from lib %d\n", i);

return 0;

}/* lib.h file */

#inndef LIB_H

#define LIB_H

void printInLib(int i);

#endifThe demo program is simple. hello.c invokes the printInLib function in lib.c to print an input number. Run the following command to compile lib.c and lib.h into a DSO:

gcc -fPic -shared -o Lib.so lib.cAfter obtaining the Lib.so file, run the following command to compile the hello.c file:

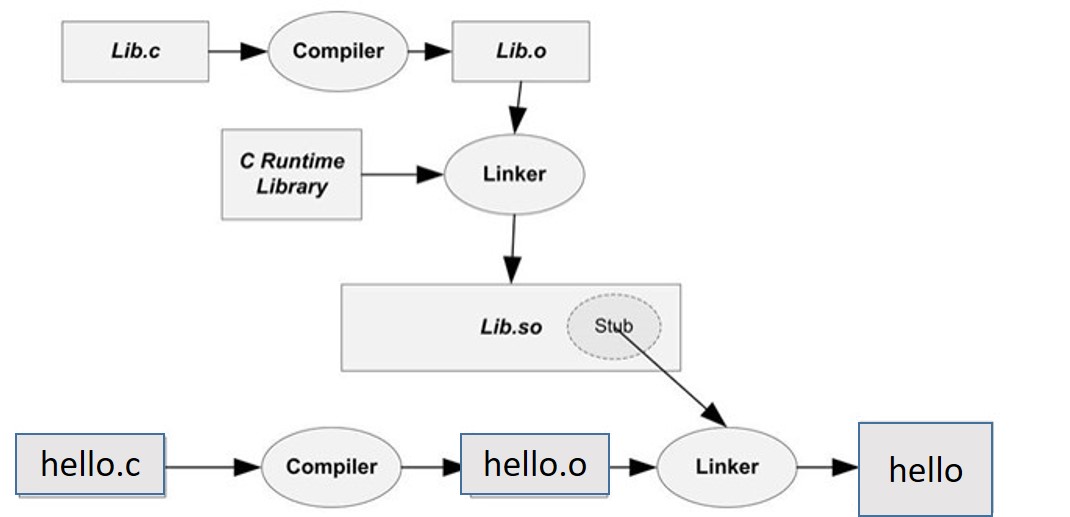

gcc -o hello hello.c ./Lib.soIn this way, an executable file hello is obtained. The following figure shows the compilation and linking process.

As you can see, when hello.c is compiled to hello.o, the linker requires the address of printInLib. Therefore, the linker needs Lib.so as input to provide complete symbol information for hello.

Note that the linker mentioned here refers to a static linker, not a dynamic linker required for program running.

Through this example, we've got a basic understanding of the concept of dynamic linking. Here is a problem: how do we determine the address of a DSO when the target program runs?

Early operating systems use static shared libraries. That is, shared libraries of all programs are managed by the operating system, and the operating system allocates an address for each library at a specific address and then performs symbol relocation according to the address.

However, this method brings a serious problem: address conflict. Consider the following scenario. Program A requires the system to load the shared libraries 1 and 2 to addresses 0x1000-0x2000 and 0x2000-0x3000. Program B requires the system to load the shared libraries 1 and 3 to addresses 0x1000-0x2000 and 0x2000-0x3000. As a result, if programs A and B are executed at the same time, either of the shared libraries 2 and 3 will fail to be loaded to the address 0x2000-0x3000. This situation becomes increasingly serious as the number of programs and shared libraries increases, and there is almost no probability for reasonable allocation.

To solve this problem, we need to think about how to load DSOs at any address. In this case, we can refer to the relocation operation in static linking. That is, do not relocate any reference to an absolute address. After the target program is loaded, modify the absolute addresses. Relocation during static linking is called link-time relocation, and relocation during program loading is called load-time relocation.

Load-time relocation can solve the problem of address conflict, but it has a great disadvantage: some instructions that need to be modified in a DSO cannot be shared among multiple processes, which loses the memory-saving advantage of dynamic linking. To solve this problem, a solution called position-independent code (PIC) emerges.

The core idea of PIC is to separate the instructions that need to be modified in a DSO and place them together with data. The instructions that do not need to be modified remain unchanged, and the instructions that need to be modified and data can have a copy in each process. How can this be achieved? The access to variables and functions in a module is simple. Relative addresses and jumps can be used.

But what about access to variables and functions across modules? "Any problem in computer science can be solved with another layer of indirection." In this case, we can create a global offset table (GOT) for these variables and functions and jump through the GOT to implement PIC. So far, dynamic linking has basically achieved the advantages we expected: more flexible, less memory and drive space usage, and more convenient for upgrade and maintenance.

Summary

The compiler generates a target file in assembly language by performing lexical analysis, syntax analysis, semantic analysis, intermediate code optimization, target code generation, and target code optimization on its source file in a high-level programming language.

The linker integrates the symbol information of each target file, allocates addresses and space, parses and relocates symbols, and finally generates an executable program. Links can be classified into static links and dynamic links according to processing methods during the link process.

Advantages of static linking

- Code is loaded quickly, and the execution speed is slightly faster than that in dynamic linking.

- We only need to ensure that correct LIB files exist on our computer. When releasing programs as binaries, we do not need to consider whether the LIB files exist on users' computers or the versions of the LIB files are consistent. This avoids the DLL Hell problem.

Disadvantages of static linking

- Executable files generated in static linking are large in size and contain the same public code, wasting memory and drive space.

Advantages of dynamic linking

- It saves memory and reduces page swapping.

- DLL files are independent of EXE files. As long as output interfaces remain unchanged (that is, the names, parameters, return value types, and invoking conventions are not changed), replacing DLL files does not affect the EXE files, greatly improving maintainability and scalability.

- Programs written in different programming languages can invoke the same DLL function as long as they comply with the function invoking conventions.

- It is suitable to large-scale software development, which makes the development process independent and loosely coupled, facilitating development and testing for developers and teams.

Disadvantages of dynamic linking

- Executable files run slightly slower than those in static linking.

- Applications that use DLLs are not self-complete. If a DLL required by an executable file does not exist, the program cannot be executed correctly.

References

- Programmer's self-cultivation - link, load and library

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Static_library

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic-link_library